Twenty-four-year-old Edward Rightor “Ned” Schowalter ’51 was promoted to first lieutenant and shortly thereafter was appointed company commander, Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 31st Infantry, 7th Infantry Division. The Korean War was ongoing, and he was assigned near Kumwha, Korea, northeast of Seoul.

On Oct. 14, 1952, Schowalter led his men toward his company objective, Jane Russell Hill. This hill was part of Triangle Hill, the overall objective of Operation Showdown. The Korean War was stalemated, and the higher-ups, led by Gen. James Van Fleet, hoped to even out the UN lines by securing the hill. Chinese forces were massed on the hilltop in bunkers covered with small arms, grenades, machine guns, and mortars.

As he moved toward the objective, Schowalter received grazing wounds to his hands and ankle. He refused medical care and pushed on. When he reached sight of the bunker complex, he took a bullet to his helmet, which saved his life but knocked him out cold. When he awoke moments later, he had a bullet in his head over his left ear. His face was covered in blood. Again, he refused a medic and continued the attack. His courage inspired his men, even those wounded, to continue the fight. Fighting was close and often hand-to-hand. At one point, Schowalter was knocked down, and when he looked up, he saw a Chinese soldier approaching him with a bayonet. Schowalter thought he would be killed until one of his soldiers placed his rifle on Schowalter’s shoulder and killed the enemy soldier.

Schowalter carried an M1911 .45 caliber pistol in one hand and a grenade in another. As he reached the bunker complex, a grenade hit close by, and he was wounded in his right side with shrapnel. His men were in the bunkers clearing out the enemy when Schowalter was hit by fire from a Chinese burp gun. His right arm was shattered, and he was knocked out for a second time. When he awoke, Chinese dead covered him. He crawled out from under the pile of death and checked on his men, ensuring that the objective was secure. Then he sought medical care.

By this time, Schowalter had been wounded seriously three times and lost much blood. He was evacuated to Osaka, Japan, and then to Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. During this period, Schowalter made a short trip to Washington, D.C., where he received the nation’s highest award for bravery, the Medal of Honor. President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented the medal at the White House in January 1954.

Schowalter was born Dec. 24, 1927, in New Orleans, Louisiana. New Orleans was hit by the Great Flood the spring prior. Over 4 feet of water covered much of the city, and it remains the most destructive river flood in U.S. history. Schowalter’s father, Edward Sr., was a lawyer with Confederate roots who came from Alabama. Edward Sr. had worked as an assistant district attorney for Huey “the Kingfish” Long, who controlled Louisiana politics with an iron hand. After being elected to the U.S. Senate with presidential aspirations, Long was assassinated.

Schowalter’s parents split when he was 11 or 12, and he was devastated. He was determined to do better with his family. After living through the Depression with his mother and younger brother, John, World War II came, and Schowalter wanted to join the fight. His parents were united that he not join but finally agreed to let him join the Merchant Marine. He was only 17. Schowalter spent the next 18 months in the galley on ships carrying soldiers back to the States from Italy. He caught the tail end of the war and was much impressed with stories he heard from combat veterans.

While this was happening, Schowalter’s father told him that he had won a few successful cases and could fund a college of his choice. Schowalter chose VMI. Nobody knows for sure why, but his family thinks an alumnus likely pointed him to the Institute.

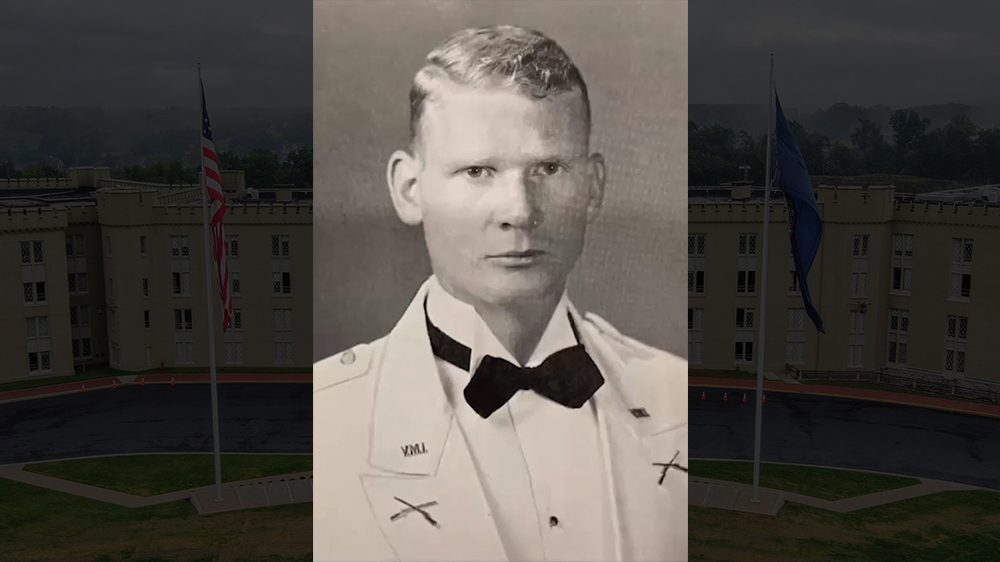

Schowalter entered the Corps in 1947 and joined Company B. He majored in chemistry, threw the discus and javelin, and filled out his full 6’3” height. Schowalter was a redhead, earning the nickname “Red,” but his family described him as having reddish-brown hair. Schowalter became a member of the 10-6-30 club for sneaking out of barracks after taps, and his yearbook entry suggested that Southern Seminary, a nearby women’s college, might name an arch after him. Schowalter was a cadet first lieutenant and distinguished military graduate who was commissioned in the Infantry upon graduation. Before graduation, Schowalter participated in a ceremony honoring retired Gen. George C. Marshall, Class of 1901.

Schowalter completed his Infantry training and headed to Korea, where his life changed forever following the Medal of Honor award. He returned to VMI in 1954, where he reviewed a parade alongside another Medal of Honor recipient, retired U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Charles E. Kilbourne Jr., Class of 1894, the Institute’s sixth superintendent. This was an amazing meeting as the two alumni received their awards 53 years apart. Kilbourne earned his Medal of Honor in 1899 during the Spanish-American War.

Schowalter was proud of his VMI experience but rarely returned to VMI and never for reunions. He disliked the attention he received because of the medal. Schowalter rejected attempts to interview him or ask him to speak. He likely would not have spoken to me, said his wife, Bonney. Surprisingly, he did not suffer from PTSD, nor did he ever complain about his many war wounds. Schowalter was a very stoic man who was not a complainer.

After recuperating at Fort Sam Houston, Schowalter was assigned to the G2 (Intelligence) section on post. During a bachelor/bachelorette event at the Officer’s Club, he met the love of his life, Bonney Milsted. Bonney was a Red Cross social worker. She had seen him often at the hospital mess hall. His arm was in a cast that pointed upward, and that, with his height, made him stand out. On their second date, he proposed, but it took another four months before she accepted. They were a great team, and they produced five children, all of whom went to college. The Schowalters made many moves, including to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and Augsburg, Germany, before returning to Fort Benning, Georgia, where Schowalter taught leadership.

Another war was coming in Vietnam, but Schowalter was assigned to Korea as a protocol officer. Before he left, he was invited to the White House with other MOH winners to meet President John F. Kennedy. The protocol job was a horrible fit for him, so he finagled a trade with another officer. He was assigned to a three-month planning team that was to increase the U.S. presence in Vietnam.

Schowalter’s assignment in Vietnam was short, but he was determined to get Vietnamese jump wings before he returned. The wind was too excessive to jump, but that didn’t stop Schowalter. When he landed, the chute was full of air and dragged him across a freshly fertilized rice paddy. The Vietnamese used human feces to fertilize, so the smell was powerful. A dyke stopped him and allowed him to extricate himself. As he was washing up, some Vietnamese laughed at him, and he joined in. They told him he was No. 1. That became a family compliment when his children learned the story. After this short Vietnam assignment, he returned to Korea to complete his tour.

His next stop was Airborne School before assuming a battalion command at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Schowalter was in his element leading soldiers and jumping out of airplanes. At the end of this tour, Schowalter talked to Bonney about volunteering for Vietnam. He felt it was his duty, especially since he had been training men who went to Vietnam. Bonney gave her blessing, and she rented a house in Fayetteville, North Carolina, while Schowalter was in Vietnam. Schowalter was assigned as a province adviser in the Mekong Delta, arriving just in time for the Tet Offensive of 1968.

Tet was a traditional celebration day in Vietnam, and North Vietnam planned attacks in all 44 provinces on Tet, Jan. 31, 1968. Schowalter was in the town of My Tho, southwest of Saigon, where his job was to advise the South Vietnamese. The town was being attacked, and Schowalter tried to get the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, also known as the South Vietnamese Army, to counterattack. The ARVN had an armored cavalry regiment but paused in the middle of town.

Schowalter couldn’t get them to move, so he started walking down the main street under fire toward the enemy, carrying his Thompson submachine gun. His Silver Star citation describes his efforts: “… facing a withering fire from small arms, machine guns, and rockets, he began to get the armored personnel carriers to move out from the cover afforded them … his valor and personal courage brought the Vietnamese Infantry behind him.” It was his example of moving alone down the street that caused the ARVN to move toward the enemy. Schowalter was hit in the neck, arms, and chest. The city was saved, and Schowalter was evacuated. The doctor told him later that he almost lost him on the operating table.

That night, Bonney received a knock at her door around 9 p.m. An old man tried to deliver a telegram, but Bonney refused to accept it. It finally dawned on her that a chaplain and Army officers would visit if Schowalter had been killed, so she accepted the telegram. It said Schowalter had “received gunshot wounds to his abdomen, left neck, and left arm with impairment to the left carotid artery and fracture to the left ulna.” His doctors demanded he be returned to the States to recover, but Schowalter worked the system and stayed to finish his tour. Bonney stayed up all night after the telegram but maintained a strong front for the children.

A few weeks after Schowalter returned to duty, Schowalter, an American sergeant, and an ARVN driver were patrolling the main highway between My Tho and Saigon when they saw a truck of Viet Cong in black pajamas. He ordered the driver to stop, and Schowalter opened fire with his Thompson submachine gun, as did the sergeant in a different direction. The driver panicked and drove off, tossing Schowalter out of the vehicle. Schowalter hid in some bushes while the enemy scattered. When the sergeant asked where the colonel was, the driver reported, “Colonel finished.” The sergeant sent an ARVN relief force to rescue Schowalter.

After he returned home, Schowalter never talked about his experiences. The children asked when they were much older, and he would share some things. In 1970, Schowalter agreed to help dedicate the New Market Battlefield Hall of Valor. This was a rare return to VMI and New Market. His son, retired U.S. Army Col. Edward R. Schowalter III, remembers that workers on top of the Hall of Valor stopped working when his dad started telling brother rat stories. They put down their tools and listened to Schowalter, sitting with their legs hanging from the roof.

Schowalter concluded his Army career in 1977. After Vietnam, he served at Fort Belvoir, Virginia; the Pentagon; and Fort Benning. He had been promoted to colonel and wore the Medal of Honor, a Silver Star, two Legions of Merit, and two Purple Hearts. The Schowalters retired to their home in Auburn, Alabama. Schowalter’s children remember him as a “fun dad.” He was very outgoing but kept few close friends outside his family.

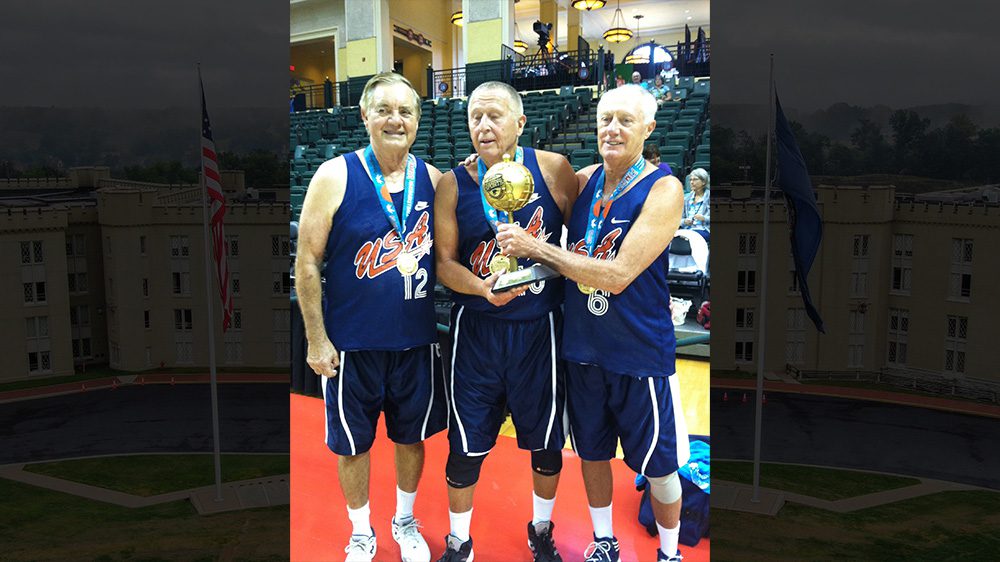

Schowalter was a great storyteller, loved to teach about things he knew well, and mentored his children’s friends. He did remain close to a couple of his brother rats. Neighborhood children gathered around their home, and Schowalter liked to play games, some of which he invented. There were bicycles and bows and arrows. Schowalter and Bonney bought a place they called the Get-A-Way, a cabin on the Chattahoochee River. It was stocked with a boat, water skis, and motorbikes. Schowalter loved hiking and the outdoors. He was a scout leader and devoted a lot of time to his children. Besides children’s activities, Schowalter grew camellias and 100 rose bushes. Late in life, he taught himself gunsmithing and shot his guns. In 2003, a life of smoking caught up with Schowalter, and he died at age 75 from emphysema. He is buried in the Fort Benning cemetery.

In 2000, his son, Edward R. Schowalter III, visited the demilitarized zone in Korea after receiving special permission to go there. He saw the hills his father fought for in Korea, which was a moving experience. The family remains close and shares their memories of a great dad and hero. Bonney still lives in her home in Auburn, surrounded by memories of Schowalter.

Col. Edward Rightor Schowalter ’51, a soldier’s soldier, was another VMI great of the 20th century and VMI’s last to receive the coveted Medal of Honor. Thanks to Mrs. Bonney Schowalter, Col. Edward R. Schowalter III, and the VMI Archives for help with this story. A moving video of Edward R. Schowalter Jr.’s Medal of Honor action can be found at the Auburn, Alabama, city website.

Author’s Note: This article was written by Jim Dittrich ’76, VMI Alumni Association historian. His research came from the VMI Archives. Thanks To Mrs. Bonney Schowalter and Col. Edward R. Schowalter III for sharing their memories.

-

Jim Dittrich ’76 VMI Alumni Association Historian