Puller, Class of 1921

Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, Class of 1921, at Guadalcanal in 1942.—Photos courtesy VMI Archives.

Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, Class of 1921, at Guadalcanal in 1942.—Photos courtesy VMI Archives.

In summer 1917, just after the United States joined the war effort in World War I, Lewis Burwell Puller, Class of 1921, reported to VMI as a rat. In his later years, Puller said that VMI “finished making a man and a soldier out of me.” Puller’s grandfather fought in the Civil War for the Confederacy and died in the Battle of Kelly’s Ford. His father also died when Puller was 10, and young Puller learned to hunt to help put food on the table. Puller knew at an early age that the Institute was for him. At VMI, he was an athlete as a “running rat,” in his words, and was promoted to cadet corporal. He finished the year without a demerit.

At the end of his rat year, Puller informed VMI that he wasn’t coming back and planned to enlist before the war in Europe ended. It was always his hope to return to the Institute. Puller enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps; went through Parris Island, South Carolina; and was on orders to Europe when the war ended. On June 4, 1919, Puller was commissioned a second lieutenant, but less than two weeks later, June 16, he was discharged, as the Marine Corps returned to peacetime and downsized. Despite this setback, Puller was still determined to serve in the Marines.

A month later, Puller accepted a commission as a lieutenant with the constabulary in Haiti. Officially, he remained a private in the Marine Corps. For the next four years, Puller learned the art of jungle fighting chasing rebel Cacos, a military group controlling mountainous regions across Haiti. In March 1924, he re-earned a commission as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. This time, he was sent to Nicaragua, where the Marines were involved in another Banana War, a name given to a series of conflicts throughout Latin America and the Caribbean from 1898–1934. Puller would earn his nickname “Chesty” and two Navy Crosses for his three years there. Few had as much combat time as he did, and he proved to be fearless in battle, always in the front where the fighting was. Puller spent the rest of the 1930s and up to World War II aboard a ship in the Pacific, as a China Marine, and teaching in the Basic School at Philadelphia.

With the coming of World War II, Puller was in command of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, and was soon headed for Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands, where the Marine Corps and 1st Marine Division were heavily engaged. The Marine Division was in dire straits without naval support. Supplies came in by air to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, and 20,000 Japanese had them surrounded. They were under fire all the time. Half of Puller’s battalion was taken away to try an end run around the Japanese west of the Matanikau River. Col. Mike Edson planned the operation with Puller as his second in command but without a real job. Puller learned that his men had walked into an ambush and would likely be annihilated. He left the safety of the headquarters and headed to the sea, where he hailed a boat. Puller made his way to a destroyer offshore, where the battle was taking place, and he signaled ashore for his unit’s boundary locations. Once he had these, Puller had the ship blast a path to the beach for his men to retreat using the ship’s 5-inch guns. Puller then headed by boat to the beach, where he helped evacuate the men while under constant enemy fire. His battalion suffered 47 casualties, but most were saved due to his spontaneous effort.

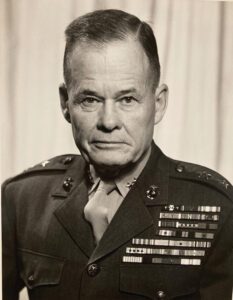

Puller commanding the 2nd Marine Division as major general circa 1954.

Puller’s battalion was reassembled and given the entire southern portion of the Henderson Field defense. The Japanese were planning a large attack, and Puller was short on supplies, so he and an enterprising non-commissioned officer went to the beach where Army supplies were piled high. They grabbed extra machine guns, ammunition, and food rations. Puller always took care of his men, and they loved him for it. The extra machine guns allowed him extra interlocking fields of fire, and he checked every position personally.

Nine Japanese infantry battalions comprising 5,600 men were headed his way on the night of Oct. 24–25, 1942. That evening, the Japanese forces repeatedly attacked his positions, breaking through in a couple of areas. Puller stayed on the front lines where men like Sgt. John Basilone held off hundreds of Japanese soldiers with his machine gun. Basilone would later earn the Medal of Honor for that night. The next day, after the Japanese retreat, Puller’s men counted 1,462 Japanese causalities forward of their position, plus 250 others found within their lines. Puller earned his third Navy Cross but had been recommended for a Medal of Honor. Gen. Vandegrift, the division commander, never acted on the recommendation. It can only be surmised that some felt Puller had too many awards already. A week later, Puller would earn his only Purple Heart of his career when a Japanese shell knocked him off his feet and peppered his legs and lower body with shrapnel. He refused evacuation until he was unable to continue in command.

After Guadalcanal, Puller, now a colonel, ran into Brig. Gen. Lem Shepherd, Class of 1917. They likely met before in China or Quantico, but these fellow Virginians got to know each other well in New Britain. Shepherd planned many of the operations and, for a time, was over Puller. Both liked to be where the action was. Puller commanded both the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines and 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, and earned a fourth Navy Cross for his actions in New Britain. Neither man stayed there long as Shepherd took command of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, which included the 4th Marines during the invasion of Guam. Puller’s younger brother, Lt. Col. Sam Puller, Class of 1922, was a regimental executive officer for the 4th Marines before he was killed in Guam.

Puller assumed command of the 1st Marine Regiment in preparation for landing on the island of Peleliu. Brig. Gen. O.P. Smith, later famed for his command during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir in North Korea, was the assistant division commander for the 1st Marine Division and Puller’s boss. During practice landings for Peleliu, he looked for Puller and found Puller’s command post forward of his battalion command post. He jokingly suggested Puller have his regimental command post behind his battalion command post. Puller replied, “That’s the way I operate. If I’m not up here, they will say, ‘Where the %&#@’s Puller?”

Peleliu was the toughest fight the Marines faced up to this point in the war. The Japanese were dug in deeply and were well supplied, not starving like at Guadalcanal. The Marines took very heavy casualties. The terrain was horrific, with no roads and few trails. Sharp rocks, crevices, and caves forced men into Japanese kill zones. Japanese machine guns, mortars, and howitzers were in abundance. Puller’s 1st Marines were finally pulled off the line with a 54% casualty rate, the highest in the division. Puller’s war was over as his previous leg wound flared up, and surgery was required to remove more shrapnel. He headed back to the U.S.

After World War II, Puller commanded the Marine Reserve area in New Orleans, then the Marine Barracks at Pearl Harbor. This was a good family assignment for Puller, who had married Virginia in 1937, and they had three young children. When the Korean War came in June 1950, Puller was sent to re-form the 1st Marine Regiment. Along with the 5th and 7th Marines, they would form the 1st Marine Division. His old friend, Smith, would be the division commander.

Puller’s orders were to move his regiment to the Korean conflict. Gen. Douglas MacArthur had created an audacious plan to land the Marines and an Army division at Inchon. The North Koreans had the U.S. and South Korean forces bottled up in the small Pusan Perimeter. Landing at Inchon could force a North Korean retreat and turn the war around. Puller led his men through the capture of Seoul. MacArthur came to decorate him personally and lauded Puller’s Marines.

After Seoul, Puller and the rest of the 1st Marine Division were moved to the east coast of Korea, where they participated in the ill-fated Chosin Reservoir campaign. MacArthur was convinced the North Koreans were all but destroyed and pushed his forces to the Yalu River, which bordered China. His faulty intelligence did not pick up that hundreds of thousands of Chinese had slipped into the North Korean mountains, and soon, the Marines were surrounded on all sides.

Shepherd, as head of all the Marines in the Pacific, visited Puller in the field that November to congratulate him on his selection to brigadier general. They had grown close over the years, and Shepherd was the godfather to Puller’s only son. Puller would soon take over the rearguard as the Marines retreated from Chosin, always under fire and in sub-zero temperatures. This was Puller’s finest moment. He extracted his men against overwhelming odds and earned his last of five Navy Crosses. He was then and remains the Marine Corps’ most decorated Marine.

After Korea, Puller would go on to lead the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune. In August 1954, Puller suffered a stroke, and although he recovered, he was forced to undergo a medical board, which recommended he retire. Shepherd told Puller that the doctors had the final say. Puller was forced into retirement with a promotion to three-star. Puller remained bitter at Shepherd and would never “forgive nor forget.”

Puller was one of the greatest leaders ever to serve our nation. He was a brilliant tactician, fearless, and admired by his men like no other Marine. At the annual 1st Marine Division Association dinner in 1952, Shepherd, commandant of the Marine Corps at the time, was addressing the association when a chant broke out calling for “Chesty, Chesty, Chesty.” Shepherd was forced to sit down until Puller addressed the crowd briefly. Puller was always outspoken and remained that way in retirement. The actor, John Wayne, would narrate a documentary story about Puller, and VMI played a part at Puller’s request. He never forgot VMI. Puller died in 1971 and is buried in his hometown of Saluda, Virginia.

Sources

Retired Lt. Gen. Lewis Burwell Puller letter to R.W. Jeffrey at VMI, Nov. 21, 1960, VMI Archives.

Davis, Burke. Marine: The Life of Chesty Puller. (Boston, Little Brown & Co.: 1962), pp. 20.

Hoffman, Lt. Col. Jon T., USMCR. Chesty: The Story of LTG Lewis B. Puller, USMC. (NY: Random House, 2001), pp. 100.