In Memory:

Dabney Coleman ’53

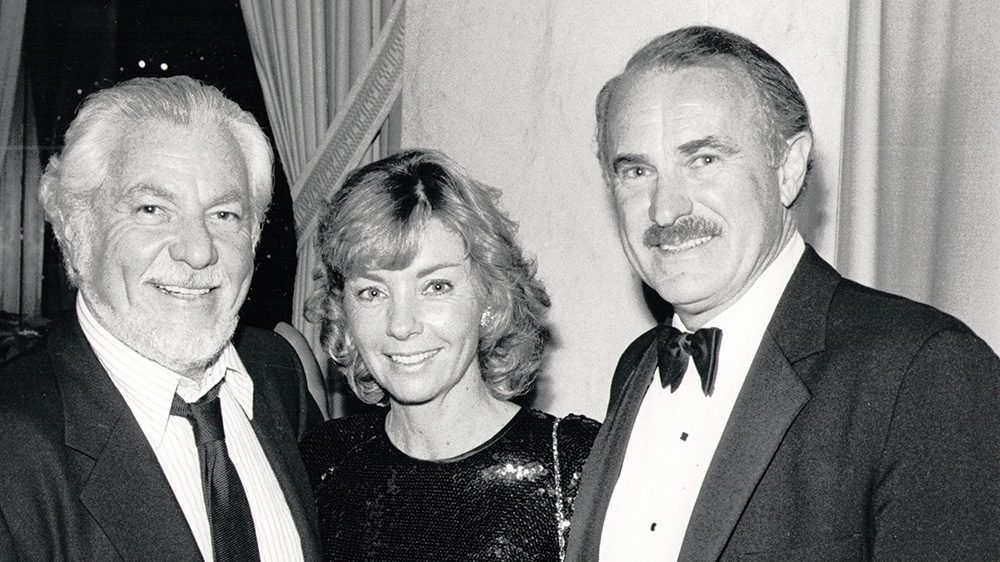

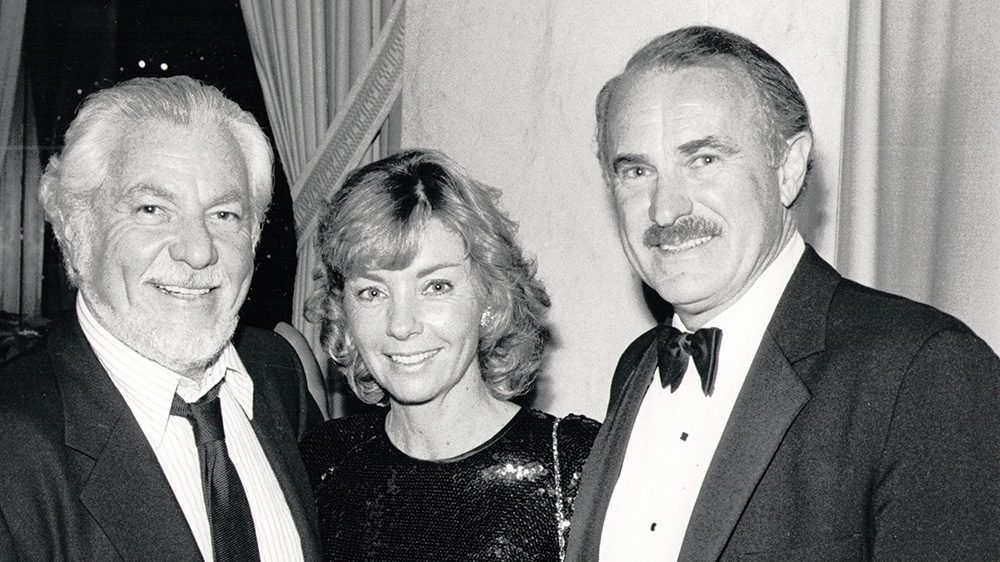

Dabney W. Coleman ’53 (right) with Bernie Brillstein (left) and Kathy Carter (center).—Photo courtesy Quincy Coleman.

Dabney W. Coleman ’53 (right) with Bernie Brillstein (left) and Kathy Carter (center).—Photo courtesy Quincy Coleman.

Dabney W. Coleman ’53, award-winning film and television actor who was the national chairman of VMI Annual Giving during the Sesquicentennial Campaign from 1989–90, died May 16, 2024. He was 92.

His father, who died when Coleman was 4 years old, was Melvin R. Coleman, Class of 1921. Coleman had other alumni relatives, as well, including an uncle, Claude D. Johns Jr., Class of 1915, and a cousin, Col. Glover S. Johns, Class of 1931, who was commandant of cadets from 1957–60. Coleman matriculated from Corpus Christi, Texas, in fall 1949, taking the train to Lexington with his mother and staying at the venerable Dutch Inn before he matriculated.

He was a corporal in his 3rd Class year. Michael Huffman ’86, who was a longtime friend, said Coleman admitted that, as a corporal, he was more than a little hard-nosed. Coleman later said he drew upon his behavior in barracks to create the archetype, described by one writer as “comedic bad guys,” for which he was widely known. He did not return after his 3rd Class year and entered the University of Texas, from which he graduated in 1953. He served in the U.S. Army from 1953–55, including a tour in Germany with the Special Services Division. Afterward, he entered law school at the University of Texas.

In 1958, however, at the urging of a local actor, Coleman decided to pursue acting. He moved to New York and enrolled at Sanford Meisner’s Neighborhood Playhouse School of the Theatre. There, Coleman met Sydney Pollack, an instructor who would later cast him in several films. His classmates included Elizabeth Ashley, James Caan, Christopher Lloyd, Brenda Vaccaro, and Jean Hale. In 1961, Coleman made his sole Broadway appearance in “A Call on Kuprin.” In the same year, he had a speaking role in an episode of the television series “The Naked City,” beginning an association with television that would last almost 60 years.

In 1962, Coleman moved to Los Angeles, California. Over the next several years, he appeared in numerous commercials and many popular television shows, such as “Ben Casey,” “Dr. Kildare,” “The Outer Limits,” “Hazel,” “I Dream of Jeannie,” and the soap opera “Bright Promise.”

In 1965, Coleman made his initial film appearance in Pollack’s first movie, “The Slender Thread.” Over the next several years, he acted in more films, including “The Trouble with Girls,” “Cinderella Liberty,” and “The Towering Inferno,” as well as two directed by Pollack. Between his debut and his final appearance in 2016’s “Rules Don’t Apply,” he appeared in more than 45 films.

By the mid-1970s, Coleman had grown his trademark mustache and, not long afterward, accepted what turned out to be a career-altering role in the syndicated show “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman.” The show, which aired from January 1976–July 1977, parodied soap operas and featured offbeat characters embroiled in ever more offbeat situations. Coleman’s role was Merle Jeeter, who became the local mayor and, according to him, “was just the worst human being.” The writers had included the character in only six episodes, but Coleman’s performance cemented it—and him—as a permanent fixture. In 2012, he described the part as “kind of where it all started, as far as people’s belief that I could do comedy—particularly that negative, caustic, cynical kind of guy. I was pretty good at doing that.”

In 1979, Coleman took the role that brought him to prominence. In the movie “9 to 5,” he played a tyrannical business executive who bullies and berates his staff, three of whom—played by Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton—engineer his comeuppance. The comedy was 1980’s second largest-grossing movie and brought Coleman widespread attention.

In short order, film producers cast him as characters who had some—often many—unattractive traits. Among the films in which Coleman played this type of character were “Tootsie” (directed by Pollack), “WarGames,” “You’ve Got Mail,” and “The Man with One Red Shoe.” When he played the lead in three movies—“Cloak and Dagger,” “Short Time,” and “Where the Heart Is”—however, he eschewed the typical Dabney Coleman role, playing instead, as his daughter, Quincy Coleman, put it, “intense professionals who found midlife redemption as fathers.”

Coleman returned to television in the early 1980s as the lead in “Buffalo Bill” and “The Slap Maxwell Story.” In them, he played, respectively, an acerbic, self-absorbed TV talk show host and an abrasive sportswriter with a talent for rubbing people the wrong way. He later played a former corporate executive serving a sentence for tax evasion as a middle school teacher in “Drexell’s Class” and was a larger-than-life magazine columnist in “Madman of the People.”

Coleman continued to turn in solid dramatic performances. In 1981, he played the romantic interest of Fonda’s character in “On Golden Pond.” He was the father of a disgraced lawyer in the series “The Guardian” (2001–04), an attorney defending a murder suspect in “Sworn to Silence,” and a murder suspect in a 1991 episode of “Colombo.” He also did voice work for animation, such as a mustachioed school principal, Peter Prickly, in the series “Recess.”

Despite advancing age and health problems, Coleman kept working. “He swore he’d never retire,” recalled Huffman. And he was true to his word. He appeared in the first two seasons of “Boardwalk Empire” as Commodore Louis Kaestner, the villainous mentor of the main character, and in episodes of “Ray Donovan” and “NCIS.” His final role came in 2019 when, in the second season finale of “Yellowstone,” he played John Dutton Sr., the father of the series’ main character. This moving performance showed that, even in his late 80s, Coleman was capable of solid acting.

Coleman received a Golden Globe award as Best Actor in a Television Series—Musical or Comedy for “The Slap Maxwell Story” in 1987 and, in the same year, a Primetime Emmy as Best Actor in a Supporting Role for “Sworn to Silence.” He collected two Screen Actors Guild Awards as part of the cast of “Boardwalk Empire” in 2011 and 2012. He received his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2014. Three years later, the International Press Academy, a Los Angeles-based association of entertainment journalists, presented him with its Mary Pickford Award for Outstanding Artistic Contribution to the Entertainment Industry.

“VMI was a force that coursed through my father’s veins. Without a doubt, VMI was one of the loves of his life.”

Quincy Coleman Son of Dabney Coleman '53

Coleman’s ties to VMI went deep. Besides his father, he had many relatives from his mother’s side who were alumni. “He comes from a lengthy line of family members who attended, and his respect and love for the Institute never wavered,” said Huffman. “He was proud of this association, and he cherished any opportunity to help the Institute.”

Most alumni remember Coleman’s role in the Sesquicentennial Campaign that occurred in the late 1980s. Gregory M. Cavallaro ’84, who would later become Keydet Club chief executive officer, recounted how it came about. “In the ’80s, when I was the director of VMI Annual Giving for the VMI Foundation, we had national chairmen for Annual Giving. As we began to organize for the VMI Sesquicentennial Campaign, Harry Warner ’57 [then the Foundation executive vice president] asked me who I thought the national chairman should be. Understanding our ambitious goal of raising $50 million through Annual Giving, I suggested we go national in scope and strongly encouraged him to invite Dabney Coleman to consider the post.”

Cavallaro recalled that Coleman announced his acceptance of the invitation “in true Coleman fashion.” Warner had sent him a letter inviting him to serve as national chairman. “Weeks went by, and we still had not heard back from Coleman. On the eve of our annual Class Agent Conference, I was watching ‘Late Night with David Letterman,’ and Letterman said, ‘We’ll be right back with our next guest, Dabney Coleman.’ I quickly started my VCR, capturing what happened next.

“Letterman said to Coleman, ‘I understand you went to a military school,’ and Coleman confirmed, ‘Yes, VMI.’ Letterman responded, ‘Oh, the West Point of the South,’ and Coleman responded, ‘No, you have that wrong; West Point is the VMI of the North.’ He then said, ‘I actually recently received an invitation inviting me to be the national chairman for their upcoming major campaign.’ Letterman replied, ‘I think you’d make a great fundraiser,’ to which Dabney responded, ‘Oh, yeah? Well, let’s see.’ He then asked Letterman for a gift in support of VMI. The audience went wild! Letterman said he didn’t have his checkbook with him. Dabney paused, waited for the audience to quiet down, and then, with perfect timing, said, ‘You don’t have $10 to give to VMI? That’s pathetic!’ The crowd went wild again. That was the first we heard that he would be a part of the campaign!” Cavallaro used the video to start the Class Agent Conference the next day.

The campaign was the first of its kind to utilize a videotape mailed to alumni and friends and a follow-up phone-a-thon. Coleman agreed to narrate the video and appear in it. Coleman returned to VMI in conjunction with this effort—first for the 1987 announcement of the Sesquicentennial Campaign and then later to do the actual filming of the video.

Huffman accompanied him on the initial visit to Lexington. “It was his first time back in 35 years. As we drove from Dulles airport, we chatted about all sorts of things. But, as soon as he saw barracks from Route 11, all lit up, he went silent. We drove straight to barracks, and he stood in [Main] Arch, taking in the sights and sounds of barracks at night. He was visibly emotional.”

“The effort was a huge success,” said Cavallaro. “We could not get videos out fast enough. We had alumni asking when they would get their video and a call from cadets.” It led to unprecedented levels of alumni support. In fact, participation jumped to an all-time high of 56.9%. VMI ranked in the Top 10 of all colleges and universities in terms of participation and was No.1 of all public schools in the country.

Coleman was proud of his role in the campaign, according to Cavallaro. At Coleman’s home in the ’90s, Cavallaro described the following scene: “After being a gracious host and getting everyone a drink, Dabney announced for everyone to head for the living room. As he reached into the TV cabinet for something, a guy yelled out, ‘Dabney, we love you, and we love VMI, but please, not the video again!’ Dabney shot back, ‘Well, you have your first drink. If you want another, in honor of my guests from VMI and Lexington, you got to watch the video!’”

In addition to hosting at his home, the restaurant Dan Tana’s figured prominently in Coleman’s social life. In fact, he visited so often that the restaurant named his favorite dish, an 18-ounce New York strip steak, “New York Steak, Dabney Coleman.” This put Coleman among such august company as George Clooney and Frank Sinatra. And at Dan Tana’s, there is a tangible mark of Coleman’s relationship with the restaurant and VMI. After a black-tie dinner at the Beverly Hilton for the campaign in the late 1980s, a large group of alumni, including Coleman, went there for what Huffman described as “a wonderful nightcap to a fabulous evening.” The owner picked up the entire tab for the group. Not long afterward, the local alumni presented the restaurant with a glass-enclosed shako with a brass plate inscribed, “To Dan, from his friends at the Virginia Military Institute.” It remains on display in the main dining room.

The end of the campaign did not end Coleman’s support of cadets and the Institute. “He’d always ask about how things were going with the cadets, and whenever he was on the East Coast, he would try to come to Lexington,” said Cavallaro. “More than anything, he enjoyed engaging cadets—and frequenting The Palms.” Coleman established a fund at VMI in honor of Glover Johns and later a track and cross country scholarship in his honor. An example of the closeness Coleman had to the Corps came in 2008 when Hannah Granger ’11, who attended VMI on the scholarship (and would later receive the Keydet Club’s Three-Legged Stool Award), did not have a date for Ring Figure. She invited Coleman to escort her, and he did.

In 2020, Coleman, who had long worn his uncle’s class ring, contacted Cavallaro, asking if it would be possible for him to receive his own class ring. “I contacted the class agent, Bill Noell ’53, and Parker Cross ’53 and made the case for allowing it because he had done so much for VMI. They agreed, and the Alumni Association sent the ring to a very appreciative Dabney Coleman in 2021.”

Quincy Coleman said of her father’s relationship with the Institute, “Along with a lifelong friendship with his roommate, James Eads ’53, VMI was a force that coursed through my father’s veins. Without a doubt, VMI was one of the loves of his life.”

Huffman remembered Coleman as a close friend. “We rarely spoke about television or movies. He always wanted to know how I was doing—personally and professionally. We would talk about his four kids and grandchildren, my family, music, sports, and VMI. He would set up dates for us to talk on the phone when I was going through a challenging time. He loved his family and made you feel like you were one of them. He was truly one of a kind—and a genius at his craft.”

Coleman was married to Ann C. Harrell from 1957–59 and to Jean Hale from 1961–83. He is survived by his four children; five grandchildren; many nieces and nephews; and sister, Beverly Coleman McCall.

The communications officer supports the strategy for all communications, including web content, public relations messages and collateral pieces in order to articulate and promote the mission of the VMI Alumni Agencies and promote philanthropy among varied constituencies.