Hayes ’49B: Inside & Over the Fence

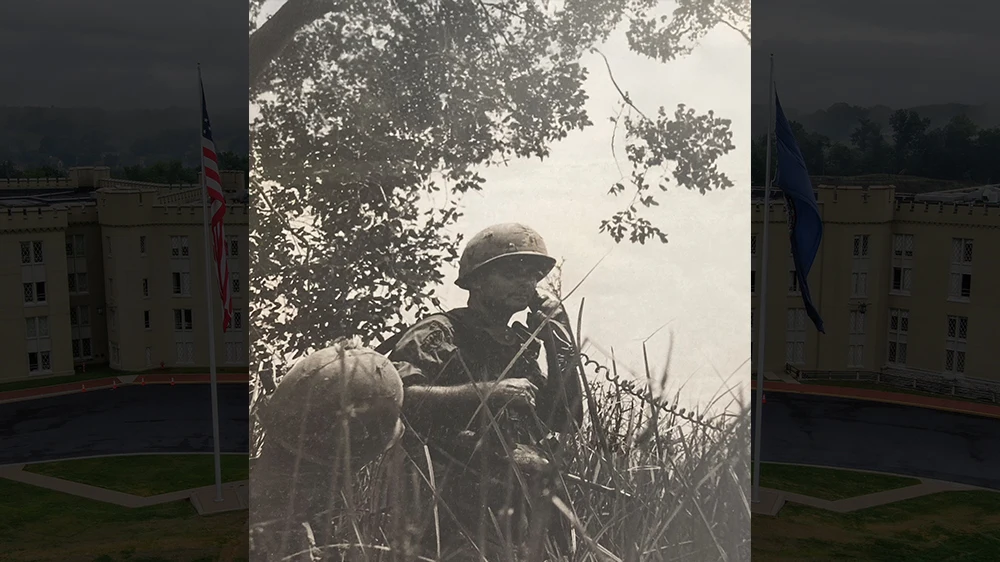

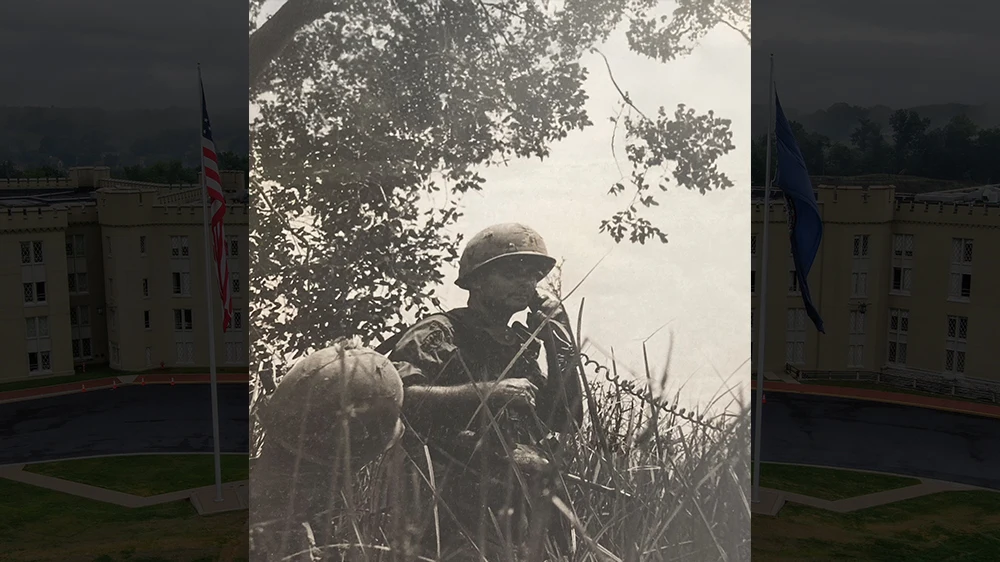

John G. “Jack” Hayes ’49B during his time in Vietnam.—Photos courtesy Hayes.

John G. “Jack” Hayes ’49B during his time in Vietnam.—Photos courtesy Hayes.

John G. “Jack” Hayes ’49B entered VMI in fall 1945. While at VMI, he learned some great lessons and made lifelong friends, but academics were a struggle. Dropping out after three semesters, Hayes joined the U.S. Army and began a 33-year career of military service, during which he would earn over 60 combat decorations, including four Silver Stars and six Purple Hearts.

Hayes was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, March 5, 1928, and at the time of publication, he is 97 years old. Raised in a military family, Hayes’ father was a career Army soldier, serving with Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing in Mexico with the Rainbow Division in World War I and again during World War II. Both of Hayes’ brothers also served in the military.

Recalling his upbringing, Hayes describes his dad’s family as being “poor from Texas.” With his father’s final Army assignment in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the family put down roots there, and Hayes began working in a coal mine and boxing. He excelled as a boxer, once even fighting a future lightweight world champion. At the time, Hayes thought boxing might be his calling, until he was attracted by the idea of a VMI education—a path his dad also wanted him to take. After leaving VMI, he enlisted with an Officer Candidate School option and was commissioned as an armor reserve officer in May 1949.

When war broke out in Korea in June 1950, Hayes was a platoon leader and second lieutenant in the 73rd Heavy Tank Battalion located at Sand Hill, Fort Benning, Georgia. His was one of three tank battalions alerted for Korea. Though they were originally supposed to deploy to Japan, the situation in Korea was critical. In August 1950, Hayes’ unit was thrown directly into the Pusan Perimeter, a defensive line around South Korea’s southeastern tip. U.S. forces had only the sea behind them, and this was Hayes’ first combat. His platoon was equipped with M26 Pershing tanks with 90mm guns, while North Koreans had Russian T34 tanks, which Hayes admitted were “good tanks.” His time in the Bowling Alley area of the Pusan Perimeter was short, as they were soon loaded on Landing Ship, Tanks, known as LSTs, and prepared for the landings at Inchon.

While Hayes was in combat, he was also on a competitive tour, which meant he had applied for a regular Army commission. He had to pass three evaluations if he wanted to commission, which was essential to his staying in the Army for a career. In addition to fighting in combat, Hayes simultaneously passed all three evaluations and earned a commission.

Hayes landed at Inchon Sept. 15, 1950, via an LST. Inchon was U.S. Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s masterful plan to circle behind the North Korean Army and break the siege of the Pusan Perimeter. At the time, they weren’t sure if the tanks would sink in the sand flats at Inchon, but, driving into water up to their hulls, the tanks made it. Hayes’ battalion was to move toward Seoul but instead joined the 32nd Infantry Regiment as they moved south toward Taejon. Hayes reported to Lt. Col. Don Faith, who would later win the Medal of Honor at the Chosin Reservoir. He recalls Faith as a nice man who cared about his soldiers, stopping every tank to wish them well as they headed out on their mission to cut off retreating North Koreans from the Pusan Perimeter.

Hayes and his wife, Paula.

Hayes’ unit soon was heavily engaged. He remembers “being scared to death,” but the trust of his company commander, Capt. Jack Doherty, gave him the strength to overcome his fear. His platoon sergeant’s tank was blown up, and Hayes’ tank was disabled. After his men got out through the bottom hatch and Doherty laid direct fire to cover them, Hayes escaped through the turret, paused, and dropped a white phosphorus grenade behind him to destroy the tank.

Next, instead of continuing to flee, Hayes ran over to his platoon sergeant’s tank and threw another WP grenade to ensure it was also destroyed. In the process, Hayes was wounded in his foot with a bullet that passed through his heel and lodged between his toes. He was sent back to the rear and treated; without X-rays to reveal the bullet, however, Hayes was allowed to return to the front with the bullet still in him. He hobbled around, and the wound soon became infected. This time, Hayes was evacuated to Japan, where the bullet was finally removed, and he would earn the first of his four Purple Hearts for combat wounds sustained in Korea.

Hayes did not enjoy his stay in the hospital, and he just left, becoming a courier carrying confidential papers back to Korea. By this time, he was a first lieutenant and rejoined his unit in time for the spring offensive in early 1951. His tank battalion was sent around the east side of Korea to reinforce the Marines, who were retreating from the Chosin Reservoir in the vicinity of Hamhung. Hayes’ service there was brief, and he returned to the western side of Korea in the vicinity of the Iron Triangle, outlined by the cities of Ch’orwon, P’yonggang, and Kimhwa.

Here, Hayes was wounded a second time—this time in the calf. After a hospital stay, he was reassigned as a recon platoon leader in the 3rd Infantry Division. Two more wounds followed, along with further assignments as a rifle company commander in the 7th Infantry Division and as a tank company commander in the 15th Infantry Regiment. In those units, Hayes served under two great commanders, Edwin Walker, who later became a major general, and Dick Stilwell, who would become a general and command all U.S/U.N. forces in Korea in the 1970s.

After 2 years in Korea, Hayes served with the 10th Special Forces Group at Bad Tölz, Germany. The 10th SFG was established in 1952, along with the 77th SFG at Fort Bragg, and Hayes joined the 10th SFG a few years later. He attended the Special Forces course afterward in class 2-57. When asked why he joined the Special Forces, Hayes remembered the heroics of the First Special Service Force that operated so successfully during World War II.

After Germany, Hayes was assigned to the 77th SFG, later the 7th SFG. President John F. Kennedy was enamored with Special Forces and asked for volunteers to go to Vietnam. Hayes signed up in 1962 and would serve five tours in Vietnam. He really liked the Vietnamese and their culture, and he learned to speak the language. He started as an adviser to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam around the time Ngo Dinh Diem, president of South Vietnam, was assassinated in November 1963. In fact, he remembers meeting Gen. Duong Van Minh, more commonly known as Gen. Big Minh, when Minh was a captain. Minh was instrumental, if not responsible, for the Diem assassination, and later, as president of South Vietnam, he negotiated with the NVA after the fall of Saigon.

Hayes returned to the U.S. from 1964–66 to serve as an instructor at Fort Leavenworth in the Joint Combined Special Operations department. He returned to Vietnam in 1966 and stayed until 1970. While in Vietnam during parts of 1966–67, Hayes commanded the Project Delta, Special Forces Operational Detachment B52. This unit was the second most highly decorated unit of the Vietnam War after Special Forces Unit MACV-SOG, a unit Hayes would one day command, as well.

Project Delta was a secret autonomous reconnaissance unit that operated within the confines of South Vietnam, or “inside the fence.” It included American Special Forces, an American Forward Air Control Section, Vietnamese Special Forces, Vietnamese Airborne Rangers, and Civilian Irregular Defense Group forces consisting of local indigenous personnel. The 281st Army Helicopter Company was attached later. This was a large organization that began in 1964 and continued through 1970. Missions came from the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam headquarters in Saigon. Army/Marine divisions or corps could request missions for deep reconnaissance in suspected enemy areas. Though dangerous, these missions were often highly successful.

Hayes recalls running missions for the 1st Infantry and 1st Cavalry Divisions, plus the Marine III MAF. Typically, he would insert a six-man team of two U.S. Special Forces soldiers and four indigenous Montagnards. The Montagnards were great soldiers who knew the jungle, the Viet Cong, and the North Vietnamese.

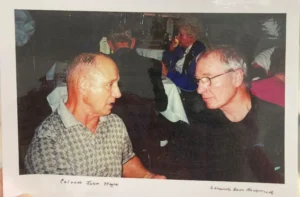

Hayes (left) speaks with U.S. Army Col. David H. Hackworth, one of the most highly decorated soldiers in the Vietnam War.

Hayes spent a lot of monitoring missions in a command-and-control helicopter, and he earned a remarkable total of 38 Air Medals during his time in Vietnam. His attention to detail made him very successful, but Hayes always credited his great teams of soldiers.

Not all missions went as planned, however, and one haunts Hayes to this day. A six-man reconnaissance team was to gather intelligence on NVA operations in the far northwest corner of South Vietnam. The team included two Special Forces sergeants, Russell “Pete” Bott and Willie E. Stark; a Vietnamese lieutenant; and three indigenous soldiers. Bott and Stark were highly trained soldiers, and it was their responsibility to select a landing zone and routes within the mission perimeters. They briefed their concept of the operation to Hayes and others involved. What they couldn’t factor in was the extreme weather that came on quickly. There was pressure from above Hayes’ level to run this mission, but the Special Forces sergeants or the aircraft pilots could cancel at any time. Usually, they would move in with one or more other helicopters landing at multiple sites to confuse the enemy as to the landing location.

When the insertion team reached the landing zone in a tall mountainous area, there was wind, rain, fog, and low visibility, but the team was inserted successfully. What they didn’t realize was that the stream they used to navigate was confused with another monsoon-swollen stream, and they landed in the wrong landing zone. They had landed in Laos at a time when the U.S. was adamant that American forces stay within South Vietnam, even though the Special Forces SOG teams routinely crossed the borders of Laos and Cambodia.

U.S. Army 1st Lt. Ed Flanagan was a Delta FAC who flew out the next day to locate the misplaced team. When Flanagan took off, the winds were at 20 knots per hour, and he was flying a small, one-engine Cessna OV-1. He had no armament nor armor protection, and this plane topped out at 120 mph. He had to fly below 500 feet to see the ground and locate the lost team. Flanagan said flying the Cessna OV-1 that day felt as “if it were a barrel tumbling over Niagara Falls.” He could see signs of enemy movement and saw a small North Vietnamese Army reconnaissance team, teams that were tasked with taking out Special Forces recon teams. He was able to get the lost Special Forces team on the radio, and he circled, hoping they would hear his engine. When they heard him, Flanagan was able to plot their location. They were near the demilitarized zone and in the middle of an NVA regiment. The weather forecast had high winds of up to 50 knots with more bad weather approaching, and Flanagan needed to return to his temporary base at Khe Sanh to refuel.

The fast-moving jet support was grounded due to the weather, but despite the dangerous conditions, Hayes set out with a team in his C&C chopper to rescue the lost Special Forces team. Hayes got the team on the radio and learned Stark was hurt badly. Bott was under fire and short on ammo. The Vietnamese and indigenous people were separated from them. Meanwhile, winds were at 50 knots—perilous conditions for helicopters and an OV-1 FAC.

The FAC found the Special Forces team and could see them in the grass at 300 feet. Flanagan heard Bott call out, “FAC, please help us. We’re hit bad.” Hayes heard this, as well, and will never forget it. Another pick-up chopper flew in for the extraction. Then, the NVA opened fire on the helicopter with automatic weapons. The chopper tried to fly off, but within seconds, it crashed in a fireball. Five U.S. soldiers were killed instantly. Bott and Stark were never found and are listed as MIA.

Hayes moved on from Project Delta to manage a studies and observation group called OPS 30 out of Nha Trang, South Vietnam. He ran classified “over the fence” missions into Laos, Cambodia, and North Vietnam. Only indigenous or tribal units could be sent into North Vietnam, and absolutely no U.S. soldiers. In 1968–69, Hayes took command of 1st Brigade, 9th Infantry Division in the Southern Delta region of South Vietnam. There, one of his battalion commanders and close friends was David Hackworth, who is credited with being one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War. “Hack” described Hayes as “a quiet, careful, methodical, and introspective soldier, just like the guerrilla enemy we were tasked to fight.” Hayes told me he kept two cobras as pets and enjoyed surprising Hackworth with them. They enjoyed playing practical jokes on each other.

After command, Hayes became a senior adviser to Maj. Gen. Hieu, commander of the ARVN 5th Infantry Division, who would later be assassinated by a fellow ARVN officer during the fall of Saigon in 1975; Hayes and Hieu became great friends during Hayes’ time as adviser. After more than 5 years in combat there, Hayes left Vietnam for good in 1970.

Following Vietnam, Hayes spent 3 years in Thailand advising the Thais, who were fighting a communist and a Muslim insurgency. In Thailand, he would meet and later marry his wife, Paula. Hayes spent his remaining years in service in staff roles, and he retired in 1982 with 33 years of service and 17 years overseas. He settled in Hayes, Virginia, which has no ties to his family but, in name, was an apt place for him to retire.

He remains a VMI man through and through. Even now, Hayes follows the Institute and remembers the loyalty and integrity that VMI gave him so many years ago. Few have seen as much time in combat as Hayes, who was authorized to wear 14 combat stripes on his uniform for 7 years in combat during two wars. On the wall of his home are the many awards he earned, including four Silver Stars, four Legions of Merit, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, 12 Bronze Stars with valor devices, six Purple Hearts, 38 Air Medals, and two Soldier Medals. Hayes’ foreign decorations are nearly equal in number.