In 2023, at 79 years old, Tom Evans ’66 wrote his last entry for the ElCap Report—a renowned seasonal climbing blog documenting the daily activity around El Capitan, the 3,000-foot granite monolith in the heart of the Yosemite Valley.

For nearly three decades, his lens captured life and death, heroic and failed ascents, and the beauty and severity of El Cap with an attention to detail, integrity, and a sense of humor that captivated the climbing world and nurtured the community around the formidable rock. With his habitual cigar, ready wit, trusted expertise, and willingness to teach, Evans became a Yosemite icon, embodying the spirit of big wall climbing culture in Yosemite.

Like an ascent up the wall, Evans’ career has been unique and winding. From soldier to engineer to 30-year high school teacher, to more random detours like cattle rancher and European tour guide, to his most recent career picked up in “retirement” as photographer and documentarian of El Cap, two constants remain a through line anchoring his every move: A passion for climbing and lessons from the Institute. Evans began his 68-year love for climbing at age 13 and his 56-year obsession with El Cap shortly after graduation from the Institute, and he says it is his VMI education that equipped his career and climbs all these years.

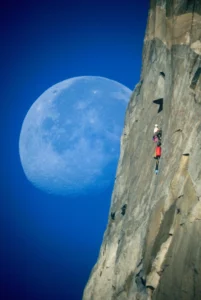

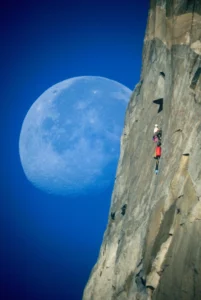

Evans, well-acquainted with the rock’s many climbing routes, knew exactly when and where climbers would emerge, allowing him to capture this shot just as the moon aligned perfectly behind them.

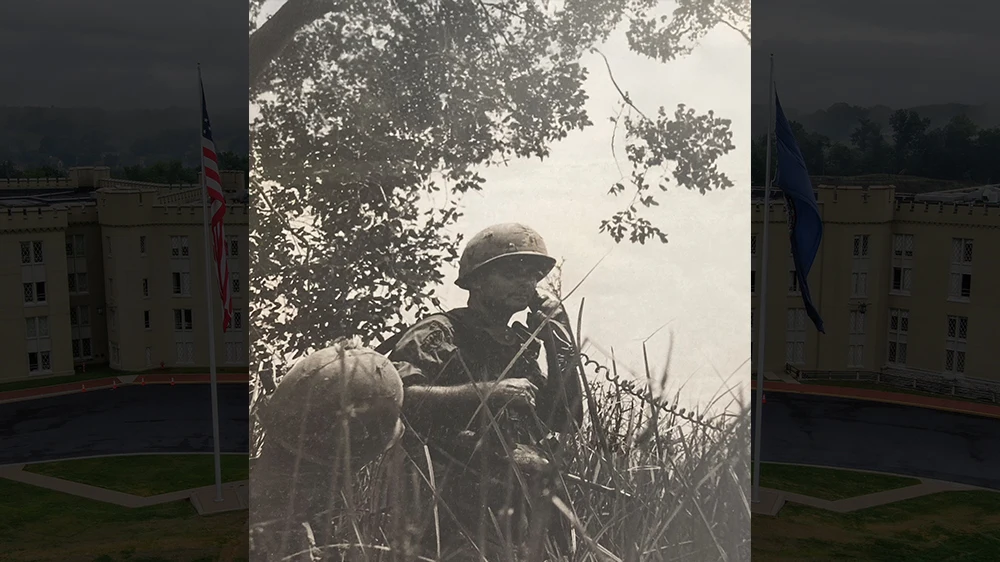

A resident of Southern California since 1987, Evans grew up in Arlington, Virginia, and became fascinated with climbing from a National Geographic article about Mount Everest at his grandparents’ home. When it came time for college, he chose VMI and graduated with a degree in civil engineering. After serving in the U.S. Army for 2 years, he began a career in engineering before deciding to become a high school physics and mathematics teacher.

Teaching was a natural fit for Evans, whose perseverance through his own academic struggles at VMI prepared him to be a gifted educator. Feeling a step behind his peers, Evans learned by saying the material out loud as if he were teaching a classroom. “By the time I actually had the opportunity to be a real teacher, I had a method so I could make people understand,” said Evans. “And that’s what I became known for in teaching—this guy who could explain things in such a way that the kids could understand it.” He loved it. Even after retiring, Evans continued to teach, educating climbers, tourists, and climbing enthusiasts about El Cap. “I’ve been a teacher all my life, it turns out,” said Evans.

During his career, Evans was climbing, and his dream early on became climbing El Cap after his first time seeing it in 1967. He was captivated. “I saw it in person, and I thought to myself, ‘This is what I’m going to do. I’m going to climb this,’” recalled Evans. Considered the peak of big wall climbing, with only the top climbers skilled enough to ascend it, El Cap requires intense preparation. In 1971, Evans made the 33rd-ever ascent of the El Capitan Nose. Today, 30-50 ascents happen each week, but in the 1970s, with evolving techniques, it was still a frontier in the sport. The climb usually takes days, with some climbers going in pairs—tied together by a rope and taking turns leading and hauling gear—while others go alone, a more dangerous and grueling feat. Climbers either scale the rock with hands and feet or use equipment to move upward.

In high-level climbing, endurance and quick thinking are key to staying alive, and Evans’ cadetship gave him an edge. “At VMI, you learn things like tenacity, pulling through when things are hard, and a lot of critical thinking. … Death is always lurking about, relentlessly waiting for you to tie the knot wrong or any number of 100 things you could do wrong,” said Evans. Physics expertise from engineering also came in handy, removing the guesswork from the equation. “I knew what forces were involved and how to make it work. Many climbers who are much better than I ever was are dead because they made a mistake or got into a situation that they weren’t aware of,” he explained.

As Evans aged, his passion for climbing evolved into joining climbers on the wall from behind the lens of a camera. In 1995, he took up climbing photography and chose to concentrate on one place. El Cap was the obvious choice. It was a convenient distance from his home with great lighting, and after all, he had a “great love for that old rock.” His first efforts yielded mostly failures, but he kept striving. Like a climb, he didn’t mind hard work and credits this diligence to VMI giving him the extra drive to get through any challenge. “VMI really made my life,” said Evans. “I would say it’s the most important thing that I ever did in my life, and it made other things easier because I was willing to be tenacious. I was willing to suffer.”

After retiring in 2003, Evans devoted himself to the craft, and by 2006, he began achieving the gorgeous, clear photos of climbers he aspired to emulate. He also moved to the El Cap bridge, which provided a great view. It was also trafficked by climbers and tourists alike. With his quality telescope and decades of knowledge, Evans was peppered with questions from climbers who gathered around him to inquire about the rock conditions and how their buddies were faring on the wall. He found he was talking all day long with no time for photos. To cut down on the chatting, he created a daily blog to share his photography, the rock conditions, and the climbs of the day. And with that, the ElCap Report was born.

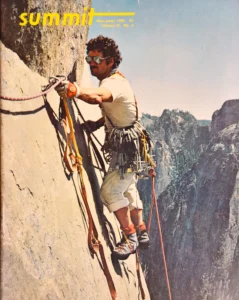

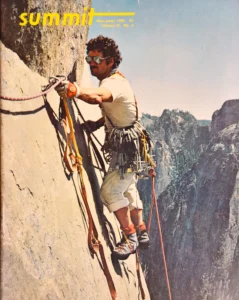

In earlier years, Evans was the camera subject on El Capitan instead of the photographer. His own ascents on El Cap have been featured in climbing magazines, such as this one from 1985.

The ElCap Report was a hit, averaging 8,000 reads per post. Some dispatches reached over 400,000 reads for historic events, such as Alex Honnold’s 2017 free solo climb of El Cap without gear or ropes. These reports revitalized the climbing world’s interest in El Cap, which had fallen off since its 1960s heyday. They were also self-funded and hard work. Evans camped out in Yosemite every year for the 6-week spring and fall climbing seasons and began each day at 6 a.m., processing hundreds of photos before trekking to photograph into the late afternoon and writing the report in the evening. Somewhere along the way, documenting El Cap became an obsession. “I had to do that report every day, and if I didn’t get that report out, I stayed up until midnight to finish,” said Evans. “That requires more than an interest or a passion; you have to have sort of a sickness. You have to want to do that so bad that you will sacrifice everything else there to do it. So, for me, it was an obsession.”

Over the years, Evans’ work became ubiquitous with El Capitan. He became the eyes on the rock—an authority and a trusted source to climbers, media, and park services. Before cell phone towers in Yosemite, park emergency services relied on Evans’ vigilant eye to spot a climber in distress and notify them. In the ElCap Report, Evans carried the values of the Honor Code, upholding truth and always being the first to point out his own mistakes, and readers trusted him. “Part of who I am is [what] I learned at VMI about honor and integrity, and all of that carries forward in anything you do, any job you work,” said Evans.

Amid the work, a favorite part of the ElCap Report was enjoying his friends on the bridge—the eclectic rabble of climbers and climbing enthusiasts—celebrating the heroes of the day who successfully summited the rock and ribbing those who had failed. He was also always ready to answer tourists’ questions—formally when he served as part of Yosemite’s Ask a Climber program, but usually just out of kindness. Eventually, Evans moved off the bridge to the meadow, and the climbing community followed, lounging in camp chairs around Evans and his camera.

In his photography, Evans’ favorite muse is a climber like himself, a person he calls the common climber, an anonymous person scaling the rock, usually on a well-traveled route. He understands what capturing these once-in-a-lifetime moments means to these climbers. “Some guy that nobody ever heard of is there—I take his picture. I like to say that the common climber—he’s my subject. He’s my guy. That’s the guy I want a picture of because they appreciate it so much.”

On Oct. 17, 2023, after nearly 1,000 posts and 7,000 photos, Evans wrote his final El Cap Report without fanfare, concluding it with: “So, that’s the way it is, on Tuesday the 17th day of October 2023,” ending with his signature sign off, “Capt. Tom.” Evans doesn’t mind the website gathering dust, but he enjoys knowing it still stands there for the “unknown, common climber, who will like to go back and see themselves in perhaps their finest moments, captured in some long-past ElCap Report. They can live that time again.” Though he could finally let the obsession go, Evans cannot keep away from El Capitan. Today, one can catch Evans, now 81, enjoying time in the meadow, reclining back with his friends, and staying late into the evening just “to enjoy the warm lighting on the cliff.”