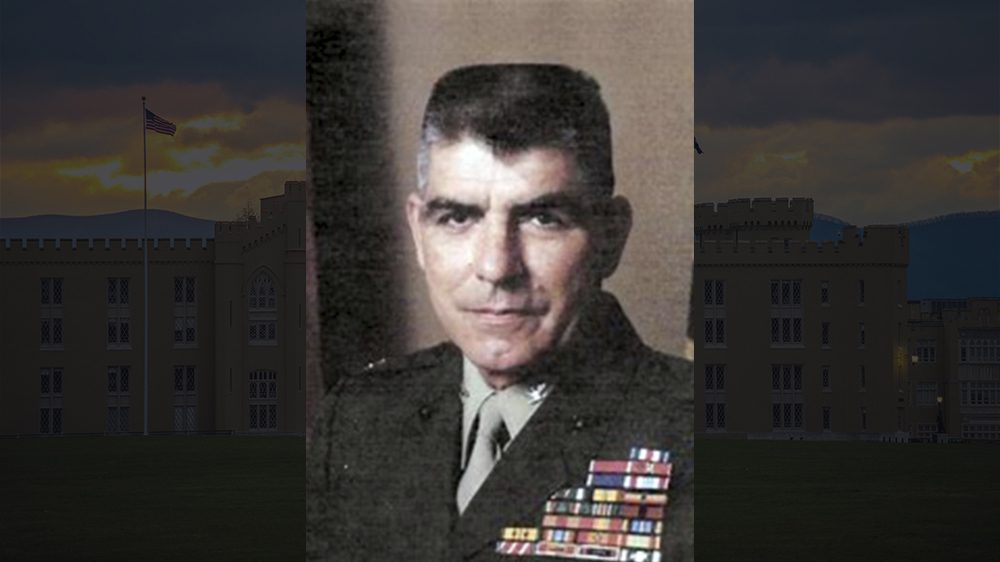

U.S. Marine Corps Sgt. Bill Dabney ’61 was in his Marine Corps uniform in 1957, attending a funeral when he met Lt. Gen. Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller, Class of 1921, legendary Marine. Puller liked to talk to Marines, so he introduced himself and invited Dabney to have lunch with him the next day. When they met, Dabney was very impressed with the depth of his knowledge about geopolitics and military history. Mrs. Puller suggested that Dabney, who was 6 feet, 4 inches tall, return to meet their tall daughter, Virginia. Dabney and Virginia hit it off and were married following Virginia’s graduation in 1961. Thus began the association between the Dabney and Puller families.

In 1957, Dabney left the Marines and joined the rat class at VMI. At VMI, he majored in English and was influenced by Col. Herbert Dillard, Class of 1934, who “made learning fun,” and Col. Glover Johns, Class of 1931, who “acted like a colonel should.” Dabney played soccer, held rank all years, graduated in three years in 1960, and was commissioned in the Marine Corps. He was a member of the Class of 1961.

There were many phases to Dabney’s life, but his experience on Hill 881 South in Vietnam was truly remarkable. In summer 1967, then-Capt. Dabney reported to the personnel office, 3rd Marine Division in Vietnam. When he saw a list of possible company commands, he picked the one furthest away from Marine headquarters. He also wanted to have the toughest assignment, so he picked one close to the North Vietnamese border.

He reported to his unit during the Battle of Con Thien. On his first day as headquarters company commander, his unit came under massive artillery fire. He spent the day conducting combat triage, designating Marines who could be saved and those who could not. He recalled this as a rough first day in combat. Con Thien was one of the major battles of the Vietnam War.

A couple of months later, Dabney took command of Company I, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines. This was in December 1967.

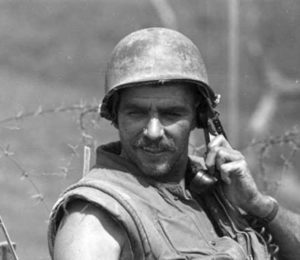

Then-Capt. Bill Dabney ’61 at Hill 881 South in Vietnam. Dabney’s unit saw heavy combat on the hill, part of the siege of Khe Sanh.—Photo courtesy Jim Dittrich ’76, VMI Alumni Association historian.

Dabney took his company to the top of Hill 881 South, and they started to dig in. This mountain top, he said, was similar in size and height to House Mountain overlooking VMI—straight up and down on three sides with a more gradual fourth side. It sat opposite Hill 881 North, where a battalion of North Vietnamese was also digging in, unbeknownst to Dabney. The hill fights of early 1967 left Hill 881 South treeless. Dabney’s outpost was the farthest west and north of any command in South Vietnam. To his west, Laos was only about 8 miles away. To the east, his mountain overlooked the Khe Sanh combat base with 6,000 entrenched Marines. Dabney’s job was to provide reconnaissance and artillery support for the main base. He had three 105mm howitzers, two 106mm recoilless rifles, and 60mm and 81mm mortars within his defense. He had emplaced razor wire and claymore mines. He was reinforced by another Marine company, Company M, allowing him to take Company I on a reconnaissance-in-force towards Hill 881 North, two clicks—or 2,000 meters—away.

On Jan. 20, 1968, he led India Company towards Hill 881 North. It was still dark and foggy with a bit of a chill. The enemy had him greatly outnumbered, as he would soon find out. Dabney sent one platoon up the right ridge, and he stayed with the left group moving up a parallel ridge. They moved through 9-foot-tall kunai grass with razor-sharp edges. His group took fire first, with significant casualties. He moved to the front, saw he had many casualties with overwhelming enemy fire, and ordered his men to pull back. A medical evacuation helicopter was shot down while trying to evacuate casualties.

Simultaneously, the platoon on the right came under heavy fire, and the young platoon leader was killed. Dabney sent the reserve platoon to assist, and that platoon leader was also killed. He had a real mess and called for heavy fire, air support, and napalm; danger close—real close. Dabney was able to extract his men and return to 881 South. He had taken heavy casualties. Under his command, Companies I and M would remain on that hill for the next 77 days—always under fire and surrounded by North Vietnamese forces.

Dabney’s firefight may have been the start of the famous 1968 Tet Offensive. He came under fire by forces that were part of an attack on the Khe Sanh Combat Base. His attack likely disrupted those plans, for the full-scale attack never occurred. Instead, three enemy divisions, a corps-sized unit, besieged the base. Senior generals feared another Dien Bien Phu, a defeat that forced the French out of Vietnam. President Lyndon B. Johnson directed that Khe Sanh would be held. During this period some of the worst fighting of the Vietnam War occurred.

Dabney’s men remember him telling them to dig, dig, and dig. Eventually, they had a trench line around his hill, not unlike the trenches of World War I. If you stuck your head above the trenches, you came under sniper fire, and mortars and artillery fire occurred daily throughout the siege. Being so isolated with only helicopter re-supply, Companies I and M were always short food and water, mail was a rarity, and sanitation was a problem. Giant rats, bigger than a small dog, ran rampant and bit soldiers, typically as they slept. Re-supply was the most dangerous part of the day, and Dabney was involved in every medical evacuation and re-supply. He calculated he had 25 seconds to unload or load a helicopter before enemy mortar or artillery landed. His men were amazed that he was not killed or significantly wounded as he ran to every helicopter. A total of seven helicopters were shot down while trying to re-supply him. The Marines needed a better way to re-supply the hill.

Dabney contributed ideas to what became an operation called Super Gaggle. The operation involved fast attack planes assaulting nearby enemy positions with bombs and napalm. This assault was followed by heavy artillery and smoke, forcing the enemy to button up and hide. Enemy artillery fires came from caves, rolling out and then back in. Relief helicopters then came in quickly and re-supplied Hill 881 South with sling loads and picked up casualties.

This was life on Hill 881 South. From January until the beginning of April 1968, Dabney and his Marines held off a superior-sized enemy that never stopped probing and firing. In the beginning of April 1968, the siege at Khe Sanh was relieved by units, including the Army’s 1st Cavalry Division, with then-Brig. Gen. Dick Irby, Class of 1939 and future VMI superintendent. Khe Sanh was abandoned shortly afterward.

Dabney lost more than 50% of his men; 42 killed and nearly 200 wounded. He proved to be the inspiration that kept the men together under such horrific conditions. For his efforts on Hill 881 South, he was nominated for the Medal of Honor. The award was downgraded because he was not wounded, according to an officer senior to Dabney. He received both a Navy Cross and a Silver Star. Dabney was one of VMI’s most decorated graduates who served in the Vietnam War.

Bill Dabney ’61 with his wife, Virginia. Virginia’s father was U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller, Class of 1921.—Photo courtesy Jim Dittrich ’76, VMI Alumni Association historian.

He returned to Vietnam for a second tour in 1971. He later commanded a Marine battalion and a Marine regiment and concluded his Marine Corps service as the head of the Naval ROTC unit at VMI. He took charge of the Naval ROTC unit in 1987, and was named commandant two years later. He retired in 1990 and settled in Lexington, where he lived out his remaining days. I met him in 2005, and we spent a few nights recording his memories, much of which is in the VMI Archives.

He passed away in 2012, and his son, Lewis, eulogized him. Lewis said his father “demanded good effort and absolute integrity. Nothing less was tolerated but with these high expectations, however, came deep love and commitment.” Col. Tom Ripley, a friend and another Marine Corps Navy Cross winner, said of Dabney, “this is a man who saw the world in black and white. He made no excuses for his absolute approach to all things. His delivery was direct without exception. He was the kind of person that you did not ask a question if you couldn’t stand the answer.”

I once asked Dabney about his relationship with his father-in-law, the famous “Chesty” Puller. “Did you call him dad?” “H@!! no,” he said. “He was either ‘General’ or ‘Sir.’” He said the general stayed out of his and Virginia’s business and was a very caring grandfather who got down on the floor to play with his grandchildren.

Dabney’s wife, Virginia, was an outstanding Marine wife and mother who took excellent care of Dabney and her family, including in Dabney’s later years, when he required constant care. Despite those challenges, Dabney always found time for family, Marines, VMI cadets, and on occasion, me, to just sit and chat. He remained active on his computer, communicating with his men through the website he created, “Warriors of Hill 881 South.” His men come together annually and for such events as Virginia’s funeral in 2018. Dabney was a remarkable man who epitomized the VMI warrior ethos.

Editor’s Note: Jim Dittrich ’76 is the VMI Alumni Association historian and a retired Army officer. He donated his interview with Col. Bill Dabney ’61 to the Adams ’71 Center within the VMI Archives. This story is based on his interviews and memories from the website Warriors of Hill 881 South.