When Jim Berger ’61 took off on his 30th mission as an Air Force pilot during the Vietnam War, he had no idea that this would be his longest flight, lasting more than six years. Jim was the backseater on an F-4C, also called the GIB, or guy in back. The Air Force used two pilots on each F-4 back in 1966. This was Dec. 2, 1966, and Berger and his pilot, Capt. Buddy Flesher, were headed to Thud Ridge, about 18 miles northwest of Hanoi. Their mission was called MiG Caps. That meant protecting an accompanying flight of bombers from MiG-17 attacks which were prevalent around Hanoi.

Berger had been in country for almost six weeks and had accrued a lot of flight time. His F-4C could hit Mach 2.2, but his plane was traveling at 913 Mach speed when a surface-to-air missile slammed into his aircraft, and he was forced to eject. Pilots say a SAM looks like a telephone pole coming at you in the blink of an eye. Ejecting at that speed was dangerous, and Berger suffered a spinal compression. That caused him to lose a permanent 2-and-a-half inches in height, and he wasn’t tall to start with. The worst was yet to come.

He landed hard and was knocked unconscious. He had a concussion. Berger awoke to find himself surrounded by angry villagers carrying bamboo sticks. They proceeded to beat him, and his arm was broken trying to protect his face. Berger was a prisoner of war.

James Robert Berger was born in West Virginia in 1938. His parents’ marriage was short-lived, and he was sent to live with an aunt and uncle on a farm. When he neared high school, he went to live with an aunt in Richmond, Virginia, and attended Thomas Jefferson High School. VMI appealed to him, and he entered in 1957, planning to be a civil engineer.

At VMI, Berger enjoyed the education and liked to tell a story about the time some of his brother rats headed out in a packed car to have some fun. He asked to ride, but only the trunk was available, so he hopped in. He left the trunk open to breathe and held it down with one arm while the other arm dangled outside. This led to a lot of honking and yelling from other drivers figuring a dead body in the trunk.

Berger spent his cadetship in Band Company, and he played the trombone. He was a cadet corporal, sergeant, and lieutenant. His nickname was “Hammy.” Berger was an active cadet—a member of the Baptist Student Union, the Religious Council, a cheerleader, and a member of the American Society of Civil Engineers. The VMI Bomb stated, “Jimmy cannot miss becoming a success because of his drive and desire to achieve the top.”

Berger served in the Virginia National Guard and Army Reserve from 1956-59. He later transferred to the Air Force Reserve in 1960. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Air Force after his graduation from VMI in June 1961. Soon after graduation, Berger married Carole Wright of Lexington, who gave Berger love and a permanent home of record. Berger’s civil engineering degree helped him get through the Air Force Base Civil Engineer Officer Course, and he served as an Air Force civil engineer in San Francisco for his first assignment.

“Jimmy cannot miss becoming a success because of his drive and desire to achieve the top.”

from VMI Bomb, 1961

Berger’s dream was to fly, so he applied, trained, and was awarded pilot wings in 1965. Next, he was sent to F-4 Phantom school before receiving orders to Vietnam. His next assignment was with the 480th Tactical Fighter Squadron based at Da Nang, South Vietnam. When he left for Vietnam, he had two sons: Bill, age 3, and Scott, who was a year old. Neither boy would remember their father, and it seemed like they met for the first time when he returned more than six years later.

After Berger was shot down, he was taken in a cage through Hanoi. He arrived at Heartbreak Hotel, also called the Hanoi Hilton. This was the main POW complex in North Vietnam. Berger refused to provide any information and was tortured twice a day during his first seven days at the Hanoi Hilton. He broke, as everyone did else who experienced this type of torture. Military personnel were trained to follow the code of conduct, which only allowed them to provide the enemy with name, rank, and serial number. Eventually, the torture broke them, and most gave their interrogators nonsensical information. One POW gave the names of the Green Bay Packers when asked for a list of his squadron’s officers. Repeated torture interrogations extracted more information, and many POWs felt they had betrayed their country. This was not the case, as the folks who wrote the code of conduct did not consider rope torture and starvation.

After those seven days, Berger returned to solitary confinement for the next six weeks. He had no feeling in his hands and arms, and his arm was broken. Berger was moved 11 times over the next six-plus years. Camps included Heartbreak, the Zoo, Plantation, Faith, and Dog Patch. He had four stays in the Hanoi Hilton. The torture continued heavily until 1969, when Ho Chi Minh, the North Vietnamese leader, died. Then the torture decreased.

After his initial solitary, Berger was given a roommate. Roommates were changed a number of times to reduce communication and possible escapes. He learned the tap code, which involved tapping on the wall using a 25-letter grid to communicate one letter at a time. The letters C and K were the same. Berger could tap in code at lightning speed even 30 years after his release.

Food was always at the bare minimum and usually included rice or bread. Soup was also a staple, usually with bits of pumpkin or cabbage, which Berger hated for the rest of his life. Prisoners never had enough to eat and seldom was there meat, fruit, or vegetables. Boils and rashes plagued all the POWs as a result. Dreams of perfect meals were always a topic of discussion. Berger weighed between 165-170 pounds when he was shot down and was 135 pounds when he returned. Before returning them, the North Vietnamese tried to fatten up the POWs, but they still came back deathly thin.

Days were spent alone or talking with a roommate. Talking was discouraged and often led to more torture. POWs were invited to interrogations, sometimes on their knees, and then there was the torture. Caged men had a lot of time to think. Some like Berger prayed. Berger’s son, Bill, shared a story about when Berger was at his lowest point. He was alone in a cell in the dark, and he was in total despair. He wanted to die. Then a light appeared in his small cell, yet there was no possible source. Berger felt God’s presence encouraging him. He was better after that.

If you ask other POWs about Berger, they may remember him as “the scrounger.” He was always looking for things and found myriad objects, like a 20-foot strand of barbed wire. This was used to bore holes in walls to communicate. He was caught communicating and was punched in the eye by a guard. Berger’s eye stayed closed for 10 days, and this injury caused later eye problems.

Berger felt he did his job and stayed true by not making anti-U.S. statements to the media. There were POW collaborators who received special privileges and better food. Sadly, these few were not punished when they returned but were shunned by the POW community. Berger remained patriotic, and as a POW, he made a U.S. flag from pieces of linen he found. This is now part of the VMI Museum collection.

Back home in Lexington, Carole waited anxiously for word about Berger. She heard nothing for six months after he was shot down. Later, Berger was able to send 11 or 12 letters home, which was very emotional for Carole. The boys knew to leave her alone after one of dad’s letters came. Carole sent Berger packages, and he received a few. The boys helped pick out what to send—often cigarettes, cards, or dice. The boys wrote to their dad, telling him about their lives but he was a mystery to them.

No one can truly appreciate what these prisoners of war went through. Hunger, loneliness, pain from their injuries, and torture were the norm. Often, they were in total isolation in 7-foot by 9-foot cells on average with rats, mosquitoes, and winter cold. In later years, POWs were put in larger rooms and classes were taught. There were church services on Sundays. Berger always had a strong faith, and his boys never saw him without a St. Christopher Medal and a cross around his neck.

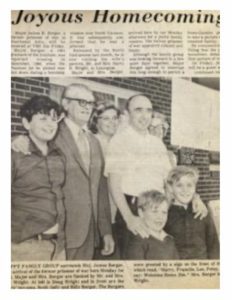

An article from a local newspaper announcing Berger’s homecoming included a photo of the Berger family. Photo provided by Jim Dittrich ’76, VMI Alumni Association historian.

Early in 1973, the POWs finally came home. VMI had two POWs: Berger and Col. Tom Kirk ’50B. Berger went to Sheppard Air Force Base, Texas, to recover from his injuries. Many POWs came home to find their wives had moved on—some had remarried, and others had spent all the POW’s money. Berger was one of the lucky ones. Carole waited faithfully for all those years and kept up the household.

When Berger got off the plane, Carole told the boys to run and hug him. This was weird to the boys because they didn’t really know him now. Berger’s first words to them were, “God bless you.” The boys never forgot that. Berger, Carole, and the boys went to a room to reacquaint, and there was dead silence. No one knew what to say, but Berger was a take-charge kind of guy, and soon the boys knew who their dad was.

Berger bought a house near Sheppard Air Force Base. One of the first things he did was set up a chair in the backyard. He invited the boys to sit down, one at a time. Bill recalls his hair barely touching his collar. This was 1973, but Berger gave both Bill and Scott a cue-ball haircut. Carole remembered that Berger liked to stay active, and when he returned, he kept the family busy all the time. They rebuilt cars, dug a garden, and restored antiques, just to name a few. Berger was a hard taskmaster, though they knew they were loved. He especially loved Christmas and was very generous to his family through the years.

Bill says he was careful around his dad because he was so stern until Bill was well into high school. One day, Bill wrecked the family VW bug and expected his dad to go ballistic. His mom said Bill had to tell him. At dinner, Bill quivered as he told dad that the car was damaged and had to be towed to a shop. Suddenly, Berger burst out laughing, which was not what Bill expected. His mom had tipped off his dad. Berger asked Bill about who would fix the car, and Bill took responsibility happily. From then on, Bill saw his dad in a different light.

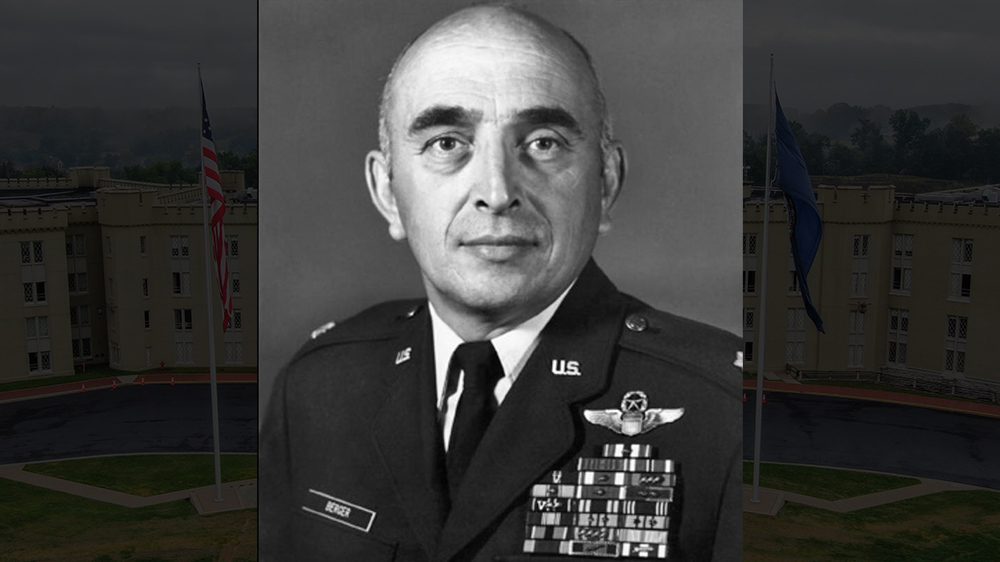

Berger stayed in the Air Force until 1984. He stood his ground on important matters and was not the favorite of some generals. He was not destined to make general, as Carole related to the boys years later. Berger commanded three different squadrons and retired as a very decorated lieutenant colonel with two Silver Stars, a Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star with valor device, and two Purple Hearts for wounds received. He was one of VMI’s most decorated Vietnam veterans.

The Bergers retired to Lexington, Virginia, and Berger bought what became Lexington Building Supply which he ran successfully for 33 years. He became quite a businessman. The family attended Manly Baptist Church where Berger became a deacon. Bill and Scott went off to college. Bill graduated with an electrical engineering degree from Baylor University and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Air Force. Berger proudly commissioned his son. Berger invested in other ventures often with his son, Scott, who—after a stint at VMI—graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in finance. Berger loved horses, and one of his investments was a horse stable. Berger kept up with his VMI brother rats and, on occasion, led his brother rats in a VMI Old Yell.

His sons continued to see the generous side of Berger. He helped a former South Vietnamese pilot who he had trained, as the man needed a sponsor in the U.S. to avoid retribution after South Vietnam fell. Berger did much more and bought the man a house. He then restored it for him with the help of his two sons. He also helped find the man and his family jobs. Later, Berger also sponsored exchange students. He was always a giving man.

Berger and Carole were very close and did everything together from bowling to playing bridge and cards with friends to square dancing. He adored her. They made every effort to make up for the time apart. Berger also loved his dogs and was thrilled when the grandkids came along.

I asked Bill if Berger suffered from PTSD, and Bill said he never saw any indication. His mom told him that his dad had night sweats for 30 years—a sure sign. Sadly, Berger was a 50-year smoker which led to COPD and cancer. He died in 2015, and Carole followed in 2018. Both boys live in Lexington and fondly remember their dad as giving, patriotic, absolute in his integrity, and a workaholic—a true VMI man. He was also someone who gave them love and set an example for his family to emulate.

Editor’s Note: This article was written by Jim Dittrich ’76, VMI Alumni Association historian, of Perryville, Arkansas. Dittrich’s sources include: Jim Berger’s sons, Bill and Scott; articles from the VMI Archives; and the online Vietnam POW Network.